JPOW: Everything Is “Fine”

Chairman Powell commented on September 18th during the FOMC news conference, “The U.S. Economy is basically fine if you talk to… business people who are actually out there doing business.” Janet Yellen, the former Fed chair, and current Treasury secretary, said last week, “The U.S. economy is strong, with GDP growth surpassing expectations and a healthy labor market.”

Further from Powell, “You can see our 50-basis point move as a commitment to make sure that we don’t fall behind.”

Historically, it is unusual for this much easing or Fed dovishness absent a looming recession, so hopefully the central bankers and economists are right.

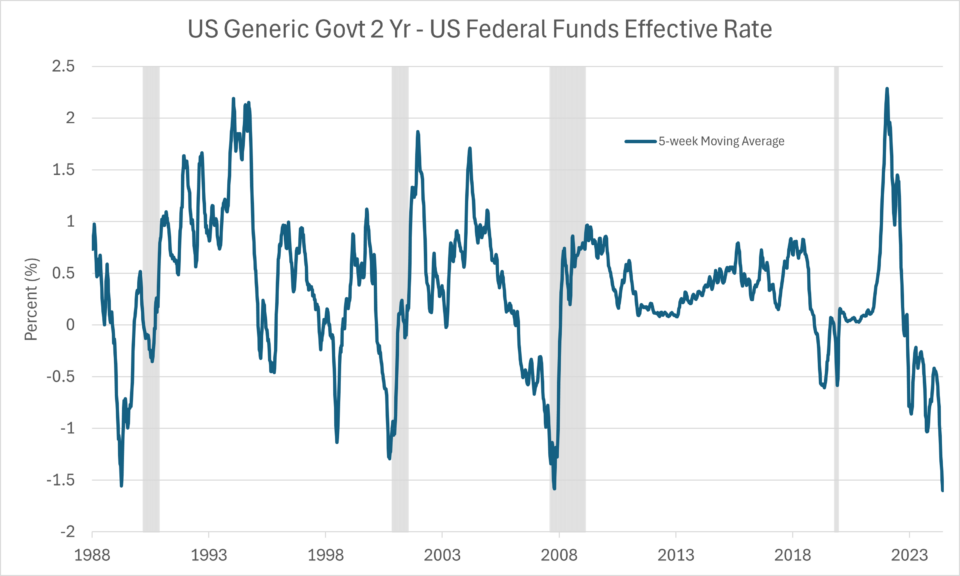

Below is our point in a chart. This chart shows the two year treasury yield minus the Fed Funds effective rate as a proxy for the number of interest rate cuts expected over the next two years. There have been five previous inversions near the current levels, including: a year ago, when the market mistakenly believed we had a recession; 2008, when we had a steep recession; 2001, when we had a slower recession; and 1989, when we had a protracted recession. We exclude the 1998 correction related to Long Term Capital Management.

In early 2001, then-Fed chair Alan Greenspan commented that aggressive cuts were necessary as the robust economy in the 90s slowed and the outlook was uncertain. At this stage, leading economic indicators dropped to contraction levels, unemployment was rising, and economic growth was clocking a negative 1.3%. We were in a slowdown. In the coming quarters, we had 9/11, a downturn in travel and commerce, and even more rate cuts. Eventually, the economy and the market recovered in 2002.

In early 2008, Ben Bernanke was in some way prescient. This was right before the greatest recession of our time. Speaking to Congress in February 2008, he expressed concerns about the U.S. economy’s performance and the increasing risk of a recession. He was right. In January 2008, he noted “The outlook for real activity in 2008 has worsened, and the downside risk to growth have become more pronounced.” Again, he nailed it. At this point, GDP was contracting -1.69% and unemployment was worsening, but most leading economic indicators were still at about 50, indicating expansion.

Interestingly, in 1989, Alan Greenspan was more concerned with inflation than the market, issuing comments like “Price stability remains our top priority, as it is fundamental to achieving sustained economic growth.” In 1990, the economy went into a prolonged recession and a five-year banking crisis, but inflation would not be an issue again for decades.

So, what have we learned from history and the responses from these oracles of the economy? It’s clear that just like most of us, they are prone to recency bias, tending to be more concerned about recent experiences (past risks) than newer developments (emerging risks). In 1989, Greenspan was focused on price stability, the economic problem of the past decade, at a juncture when he should have been more concerned with economic growth. That said, it does appear that Greenspan in 2001 and Ben Bernanke in 2008 were essentially right with their conclusions. Generally agreeing with the bond market that aggressive action was needed in response to a slowing economy.

In the case of JPOW, his comments suggest “mission accomplished” with inflation behind us while the bond market is signaling, at least based on history, that we are likely entering a recession or in need of potent stimulus in the form of lower rates. Potentially, his recency bias is that we avoided a recession a year ago and that we appear to have lower inflation in the most recent data, so those are the right concerns to fight for rather than the apparent economic slowdown as we enter Q4. Is JPOW manically focused on his engineered soft landing? It appears to be so.

We are surprised that the Fed doesn’t sound more like Fed Governors of the past when the economy was slowing. The risk here is that the bond market has already discounted a sharp slowdown in the economy and yet the Fed is saying we are just cutting a bunch just in case things are worse than we thought. The Fed is in search of a perfect hedge. We see primarily two possible outcomes, the economy has a soft landing with no issues on its way to improving economic conditions in the second half of next year, if that happens and we have no inflation concerns the Fed will have been right in spending a cautionary bullet early.

If, however, they are wrong in either direction, hard landing or inflation, the Fed has now poorly forecasted the economy and appears to be naive to risks inherent most of the time for an economy. A bullet would have been wasted or a message extended to the markets too early, becoming the boy who called wolf or even worse, the boy who could not call the economy well.

We are still in the camp that a central banker should be seldom seen or heard and that the risk increases the more often they are needed to stave off liquidity of volatility crises that effectively dampens short term volatility, but this type of smoothing behavior will spike the volatility in a true crisis as a central banker’s voice is less trusted.

In the words of Paul Volcker, “We know there will be distortions. Nobody knows how to measure these distortions.” In our opinion, this rhetoric feels more appropriate today than spending time claiming victory over inflation and a soft landing.