“No Mas” Private Equity

The TwinFocus research team has met with hundreds of private equity managers over the past decade-plus. We have compared the returns against public peers. We have applied good old common sense. Our views on private equity have softened. In the words mouthed by Roberto Duran against Sugar Ray Leonard in their famous fight “…No mas.” Like private equity, Roberto had quite a run leading up to that day, but even he eventually said no more.

First-hand experience in the largest Private Equity/LBO transaction in the late 80’s

Years ago, as a young engineer, TwinFocus’ Global Strategist, Dave Daglio, was part of a management and development training program at RJR Nabisco. In Dave’s words, “the program was extraordinary”.

This past summer, Dave, as the eloquent raconteur that he is, described to our Research Team a fascinating story while at RJR that helped forge the path of his career in finance.

“We traveled across the country, working in factories with built-in mentors. Once a month, we flew back to corporate headquarters nestled on a recently renovated golf course for week-long sessions on leadership. We networked with firm leaders, heard from motivational speakers, and learned from organizational experts worldwide.

In some ways, the job felt more like an extension of academics – with unlimited Oreos – than a “real job.” It was a sign of the excess at RJR Nabisco and foreshadowed the events that would rock my world just nine months into my first real job.

Originally, I was part of a global team of engineers tasked with spending billions on factory upgrades and automation. The idea was to channel the enormous cash flows from Nabisco and tobacco profits into the future.

It was an engineer’s dream: overhauling factories that had seen limited improvements in 40 years. As engineers, we were entrusted with billions to rebuild these adequately performing factories.

Then, the bottom fell out.

KKR bought us, and the first thing they did was shelve my training program. Next, they grounded the private jets that executives and new hires sometimes used and froze all non-urgent capital spending.

It felt awful then, but now, after 30+ years in finance, it makes perfect sense.

KKR was right. The old factories were good enough. Private jets should be used sparingly, and a training program costing five times my salary wasn’t a good investment for the firm.

I was offered a “real” job, working as a manufacturing engineer in a 40-year-old plant in New Jersey, with a capital budget one-tenth the size of the previous one. No fancy meetings, no expense reports, and no exposure to leadership. It was clearly not the same job I had months earlier.

This began my fascination with finance. How could a firm I had never heard of take over one of the largest companies in the world and immediately know how to cut costs so efficiently?

In some ways, I had a firsthand seat at the table of financial innovation. I was sitting at the intersection of financial engineering (taking on more leverage than conservative management teams did) and clever insights on improving a 100-year-old business. Watching was magical, even if my day-to-day went from training sessions to a real job.”

Has Frosting Been Licked Out of PE’s Oreo?

The investment story of taking on leverage and improving operations has been a tale since even before RJR’s fate (and the orator of the story) in 1989. But today at TwinFocus, we are asking: Has enough been done? Has most of the frosting been licked off the Oreo?

Our Conclusion: we are more certain than not that most private equity investments will return less than public equities over the coming decade after fees and taxes.

It’s a perfect cocktail:

• the starting point on valuations are high;

• opportunities for further returns from leverage are diminished, particularly as the cost of leverage is elevated; and

• fees are extremely high and tax efficiency for US UHNW taxable investors is lacking

We believe the likelihood of investors capturing an “illiquidity premium” from private equity is quite low.

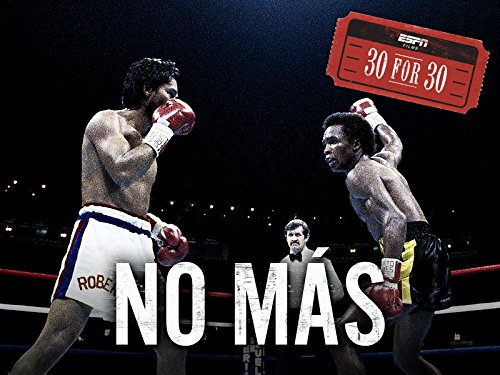

Based on JPM’s annual report, we calculate that private equity, private debt, and direct financing through endowments/insurance companies now dwarf traditional bank lending. Others have calculated that PE controls more assets than the entire Russell 2000’s market capitalization. So, this once tiny asset class has more importance than most and more importance than in the late 1980s.

Most clients today ask not whether to invest in private equity but rather how much to invest compared to other risky assets and parameters around illiquidity budgets.

Our view has changed considerably. Today, we believe you should own much less than normal and be highly skeptical of most broad-based claims of the illiquidity premium, particularly if you are a high tax bracket UHNW investor.

We suspect that the current illiquidity “premium” is zero, or even negative, and investors are largely paying high fees for the “opportunity” to avoid the volatility of daily marks in the public markets.

In our mind, that is a lousy tradeoff. We would rather make money, even if it comes with the apparent volatility of public equities.

Our conclusions are based on the following insights:

1. Manager Meetings and Direct Investments: We meet with hundreds of private equity managers each year, see hundreds of direct / co-investments from private equity sponsors and the like, and analyze the relative relationship between public equities and various transactions. This leads us to believe that, on average, private investments are generally marked in line with public market comparables, and no longer at a discount, unlike in the early days of private equity, when discounts were as large as 50%. As such, investor starting points are disadvantageous headwinds from the onset.

2. Return Information: We now have a large body of return information that leads to an obvious conclusion: PE returns ex-post are heavily influenced by the flows going in at the time (vintage).

Simply put, if one invests in PE when capital is exiting the space, the returns have been strong. When it is well-liked and “so crowded no one goes there anymore,” the returns are sub-par. The issue is that as humans, we like to follow the crowd.

In 2008 – 2011, when nobody wanted to invest in long-tail and illiquid assets like PE, it was truly a once-in-a-generation opportunity, yet few took the chance. Today, that is not true, as demand for PE funds is still soaring. This has created an obvious tension reported by almost every manager we meet with, the struggle to put capital to work at reasonable prices.

3. Tax Impact: Taxes eat at returns due to the lack of deductibility of management and other fund fees. As returns drop, the after-tax returns ultimately realized by clients fall at an exponential rate. Management fees, in general, are not deductible, so as gross returns fall, the tax burden increases as a share of total returns.

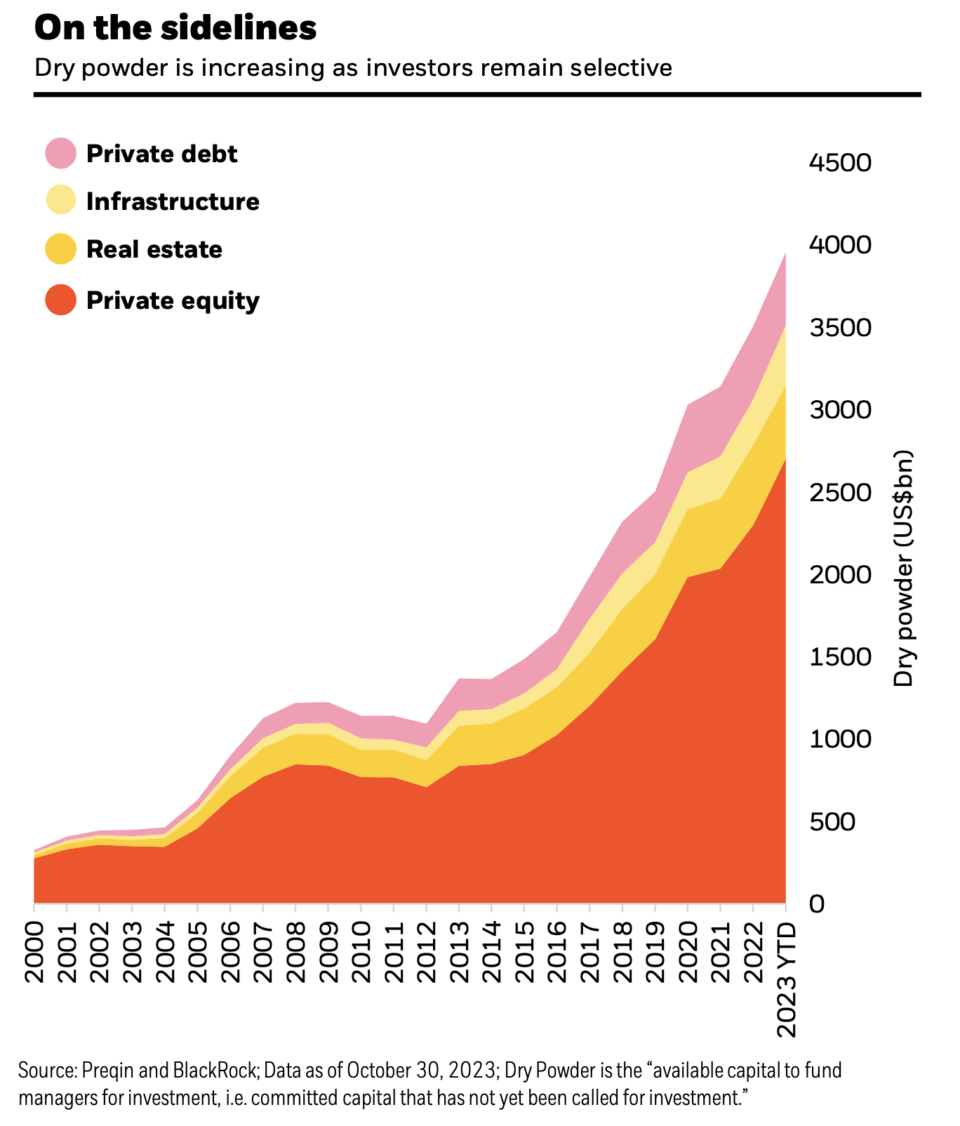

4. Illiquidity/Skill Premium: Over the last decade and a half, the “skill” or added returns from PE management is about 1% net of fees over public market investments. Anecdotally, the tax-drag from management fees more than absorbs that skill premium.

Abstracting PE Returns

We love abstractions. It is the way we drive a car. To drive a car, you only need to know a few things: gear, acceleration, steering wheel, and brakes. Underneath that abstraction is a blizzard of items: piston pressure, oil levels, timing belts, slip differential. None of this is needed to drive the car. The same can be said about forecasting the average return of private equity.

PE net after-tax returns can be summarized as the following:

1. Growth in earnings of the asset;

2. Plus, benefits from exit multiple vs. entry multiple;

3. Plus, benefits from leverage; and

4. Minus fees and taxes

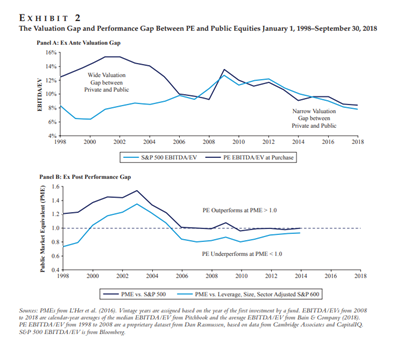

We have deconstructed the profits of the small-cap universe as a proxy for the profit growth of the average company owned by private equity firms. We then compared that against the benchmark for PE returns since 2006 and extrapolated the returns from skill (illiquidity premium and operational improvement) to our assumptions about the returns from leverage and valuations over the last decade and a half.

For leverage, we assumed 50% debt (average over the time frame) at a rate equal to the average rate since 2007, and for multiple expansion, we looked at the annual change of the average LBO multiple for the same time period.

Combining our assumptions about the markets, we then extrapolated the added value of PE compared to owning just an average company in the S&P 600.

Below is the result of our deconstruction of the returns using the PEBUY index and the S&P 600 index as a proxy for profit growth:

We start with an average S&P 600 company’s EBITDA growth (10% since 2007, excluding financials) as a proxy for the profit growth of private equity companies. We then assume a 1.4x multiple expansion (which equates to a 2% addition to returns) discerned from private equity annual reports and other datasets and assume accretion from typical leverage of 3% given the average growth rates and cost of debt since 2007. Finally, we remove 2 and 20 fees, and then compare the net returns of this abstraction versus the actual returns from the PEBUY index. The difference is 1%. In other words, the illiquidity premium for holding the average PE firm has led to just a point of extra performance since 2007. And on an after-tax basis, that premium is fully absorbed by the tax inefficiency of the vehicles used to invest in private equity – not to mention that this tax inefficiency does not exist in public market peers.

An analysis was done by Cambridge Associates from 1986 through 2017, highlighting that returns are about the same as 1.2x the Russell 2000 index as a proxy for their leverage and firm size, as well as small-cap value stocks under the Fama-French model.

Yet another study was done by Ilmanen, Chandra, and McQuinn (AQR) in their paper “Demystifying Illiquid Assets – Expected Returns for Private Equity,” in which they conclude that “private equity does not seem to offer as attractive a net-of-fee return edge over public market counterparts as it did 15-20 years ago from either a historical or forward-looking perspective.” This paper also conjectures that the greater attraction to private equity is “investors’ preference for the return-smoothing properties of illiquid assets in general.”

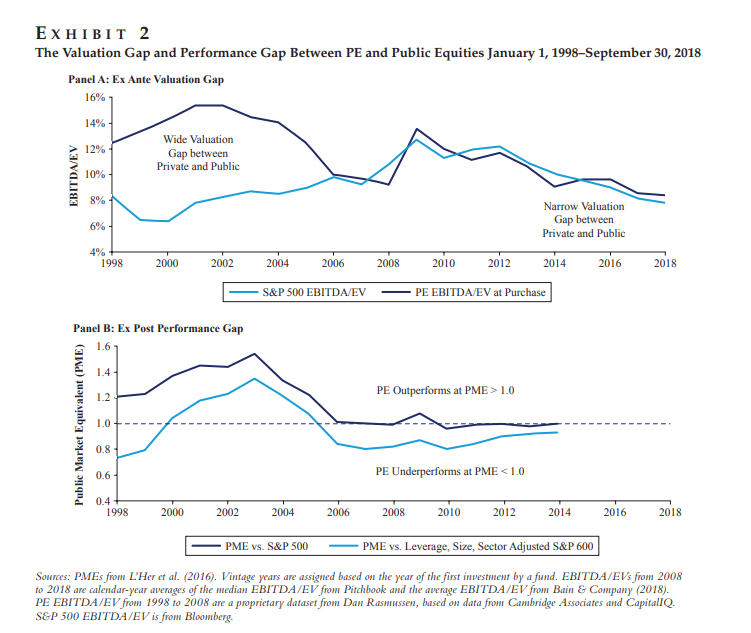

In our view, the most important takeaway from their work is that while historical returns of PE were exceptional for vintage years in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s, returns since then have been less exceptional and that starting valuations matter most for final investor returns.

The Starting Point Matters Most

For years, private equity firms were able to buy assets at a large discount to public valuations, take on a few turns of leverage, hold for a few years, and sell at higher valuations. In general, this was clever work and valuable to investors, while making managers lots of money, charging fees on gross investments and incentive allocations on exits.

In the early 2000s, for example, the S&P 500 traded around 15x EV/EBITDA, while the private markets traded around 7.5x EV/EBITDA. Even if the average PE company only grew at ~4% a year (GDP), if a PE firm could close and realize this valuation gap in a seven-year period, with the assistance of some cheap leverage, it could comfortably generate 15%+ returns annually.

Over-simplified math:

• EBITDA Year 1: $10mn

• Private Purchase Price: $75mn ($37.5mn LP Equity, $37.5mn Debt, 7.5X

• EBITDA Year 7 (4% Annual Growth): $13mn

• Sales Price Year 7: $197mn ($159.5mn Equity, $37.5mn Debt, 15.5X)

• Cost of interest (7 years @ 6%): $16mn

• 2 & 20 fees: ~$30mn

• LP Equity after fees and interest: $113.5

Annualized Net Returns: 17.1%

This is an exceptional return, and if we were at the same starting point on valuation, we would likely recommend continuing to be overweight to the illiquidity premium. However, we believe the starting point is different today.

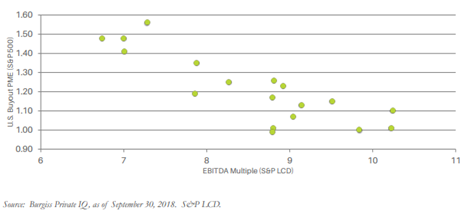

1. The AQR paper we mentioned earlier included the chart below (which is also where we obtained our valuations for the math above). Their data shows (and our belief is) that valuations are now close to parity with public markets, so the valuation jump is less likely. For context, if you get rid of the valuation expansion in the model above, returns are effectively zero…

2. As starting valuations are higher, the returns of PE are lower. It is common sense, but it is jarring to see the correlation.

3. In addition, while subjective, the recent buying spurt of PE firms taking public companies private seems to indicate that the arbitrage has narrowed. The data of true comparison is lacking, so take this as just our intuition based on hundreds of discussions.

This indicates to us that public companies are at least partially more attractive than some of the targets available in the private markets.

Things Have Changed – Our Forecast of Returns:

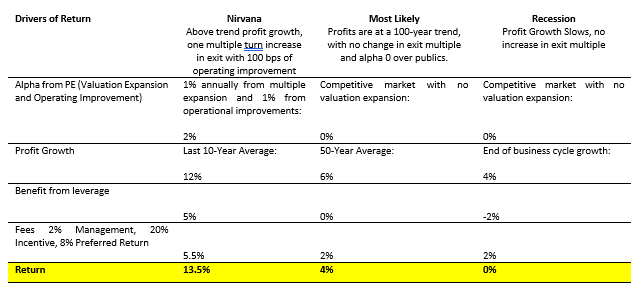

Now, if we assume that over the next 7 years a) the duration of many PE funds, b) profits grow in line with the 100-year average of corporates just above nominal GDP, c) exit multiples don’t change, and d) the benefit of leverage is about the same as last decade, this would equate to forecasted 4% net (pre-tax).

The scenarios below show Nirvana as it has been for the last ten years. They most likely use a common-sense forecast. The recession assumes below-trend profit growth, assuming we are later in the business cycle.

Based on reasonable forecasts, we believe the nirvana scenario is unlikely, as much of the liquidity premium reflected in low valuations in privates is no longer prevalent. In addition, with the enormous scale we now see, we are skeptical that “alpha” is available.

In other words, if PE-acquired companies grow profits in line with the average company and the exit multiples do not increase, single-digit returns are likely after fees.

Leverage Buyouts a/k/a Private Equity

RJR Nabisco was purchased near the peak of the then-called LBO boom. The results were terrible for investors. Based on published reports, returns are near 0% or negative returns over the decade-plus holding period.

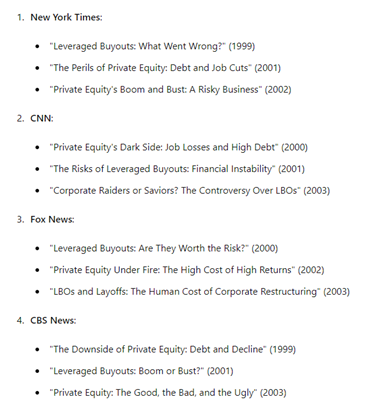

If you read our papers recently, you know we have enjoyed the use of AI in our writing – and we once again asked for a summary. Chat GPT’s assertion is that “LBOs gained a somewhat negative reputation in the 1980s due to some high-profile failures and criticisms of excessive leverage. The term ‘private equity’ helped distance the industry from these negative associations.”

Not surprisingly, a search of headlines from the late 1990s through the early 2000s (just about the time RJR was being monetized by investors) saw a quite sanguine tone.

Today, the headlines are quite positive for PE and its return outlook. Again, we ask GPT what it thought about the expected returns for Private Equity going forward:

Today View from GPT

“Consensus among analysts and industry experts suggests that while PE is likely to continue offering attractive returns relative to public markets, the days of outsized returns may be harder to sustain due to high valuations, increased competition, and macroeconomic uncertainties. Return expectations may be more modest compared to previous cycles, but PE still remains a strong asset class for long-term investors seeking diversification and higher yields than traditional equity markets.”

Scale is the Enemy of Returns

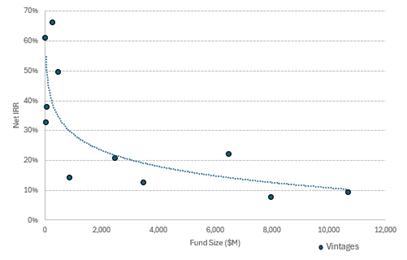

We also suspect that scale is an enemy; while there is scant proof on average that scale hurts returns, we do have returns from one of the most widely recognized private equity firms scaled against the assets under management (we have purposely excluded the identity of the manager), but the take is quite clear, more assets translates into lower returns. The second take is that if you had invested in their funds in the late 1990s and early 2000s when the average fund size was less than $1 BB and the mood was toxic to LBO/PE, the returns were exceptional – 30 to 60% – worth the risk and the liquidity premium. However, the returns as the firm scaled have dropped almost linearly.

Summary

The starting point for the valuation of acquired companies is high, the fees remain substantial, and the benefits of quantitative easing are behind us. On the margin, the scale has reduced returns, and the players are just tremendous. As a result, we suspect that returns from private equity will be lower than most expect, particularly for tax paying investors. While our assertion could be wrong in numerous ways, it is more likely than not that private equity returns will not meet investors’ expectations over the next decade.

That said, we do believe that there are exceptions to the general private equity rule for those managers playing in very esoteric markets with laser-focused discipline on how they buy, what they buy, how they operate and add value, and how they exit. However, even for these managers that are clearly distinguishable, our hurdle for investment remains much higher, particularly when we factor in US taxes and management fees.