U.S. Trade Policy in Focus: Understanding the Historical, Forward Looking, and Market Impacts on Global Commerce and Asset Classes

Executive Summary

- This paper analyzes tariffs, their historical context, advantages, disadvantages, and alternative policy measures. President Trump intends to use tariffs as a tool for economic policy and national security, aiming to increase revenues, lower trade deficits, and enhance US leverage.

- Post-World War II, the US led the creation of an international economic order, benefiting from globalization, fostering international alliances, and the gradual lowering of tariffs across the world. The globalization movement reduced poverty and fostered a global middle class, but recent US trade policies threaten this framework. During this period, the US has dominated technological innovation and has enjoyed large trade surpluses in services, adding millions of high quality, value-add jobs. During this period, the US has seen its manufacturing sectors shrink, as have all the other major developed economies across the world – even those that arduously tried to protect manufacturing.

- From a national security perspective, tariffs are seen as a response to China’s economic rise and the decline of US manufacturing, with the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbating and highlighting this demise and the supply chain vulnerabilities. Two schools of thought have emerged in integrating economic policy into national security: government support for industry and protectionist measures. This paper will analyze how China’s current economic growth model is outdated and the leading cause for may of these global imbalances. A foreign policy that does not directly address these imbalances in a multi-lateral fashion is destined for failure.

- Tariffs can protect domestic industries but also lead to higher consumer prices and economic distortions. Retaliatory tariffs and currency manipulation and adjustments can neutralize intended benefits and harm exporters, as was the case with the 2018 tariff program adopted by President Trump and continued under the Biden administration.

- Tariffs alone are insufficient to address trade imbalances, which are influenced by macroeconomic factors. China’s trade surpluses are driven by government policies and institutional rigidities, requiring far more complex strategies, needing a multi-lateral and globally coordinated effort, which can be exacerbated with unilateral tariffs.

- A strategic approach includes increasing domestic savings, smart immigration policies, and negotiating fair trade agreements. Bolstering alliances, cooperation with allies and targeted subsidies can strengthen key sectors and national security overall, without imposing heavy costs on consumers and exporters, and without harming the international order that has allowed the US to prosper.

- Tariffs can influence international relations but may also escalate tensions and disrupt alliances. Protectionist policies have not achieved their objectives and have led to unintended economic consequences.

- Trump’s tariffs against Canada aim to force submission but appear to have provoked a nationalist response. Canada is a vital ally in security and intelligence, and strained relations could have long-term implications.

- Tariffs have been used to achieve economic and national objectives but often introduce inefficiencies and unintended consequences. A more strategic and targeted approach to trade, focusing on diplomacy, innovation, and selective policy instruments, is the more optimal approach.

- To assess the potential overall impact tariffs can have on the US and global economies, some of the geopolitical variables we are monitoring very closely include:

-

- Tariff Design & Implementation. Implementation of US tariffs and the retaliatory response of our trading partners.

- Immigration. Whether this administration will deport 500K to 1.0 MM of the undocumented migrants with criminal records, which should have minimal impact on the overall US economy or 8 MM to 10 MM of undocumented migrants, which can have profound impacts on certain sectors/industries (i.e., construction, agriculture, hospitality) as well as the overall US economy.

- International Global Order | Trading Systems & Alliances. How much will the US alienate our trading partners and major alliances that the US has fostered over the previous eight decades.

- US – China Relations. Well beyond the scope of this paper, this is perhaps the single most important geopolitical variable that will influence geopolitics for the rest of this century in terms of global order and the direction of the US economy. Just as that pivotal moment in 2001 had profound impacts on the trajectory of Chinese manufacturing and export economy and the de-industrialization of the US economy, the next three years will most likely guide the direction of geopolitics for decades to come, particularly if we have some type of invasion in Taiwan during this Trump administration.

- India & Global South. In addition to China, India and Narendra Modi’s global policies will be another key variable in global geopolitics, as well as whether India will be able to resolve long-standing issues with China or will migrate more towards western values. Additionally, the Global South and the rise of the “Middle Powers” will be on our radar, as we move from a unipolar world to one where the Thucydidean framework between US & China is met with a possible neutral party, being the rise and influence of the Middle Powers.

-

- Areas of Investment Interest. In light of the center-stage importance of geopolitics, areas of interest for investors and investment portfolios would include:

-

-

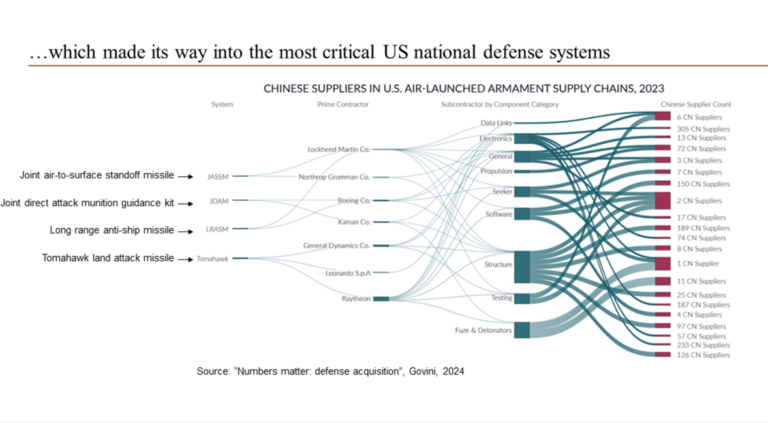

- Defense Spending. Defense spending across the world will be on the rise for years to come, particularly in Europe and Asia. Given the infiltration of China’s supply chain in our key defense systems, the US, with the support of both sides of the political aisle, will heavily subsidize the defense sector in terms of producing new and innovative technologies that further US national interests. As such, we will see tremendous opportunities for investment in both public and private markets that we are actively pursuing.

- US Agriculture. Should other trading partners implement retaliatory tariffs, as they did with US tariffs in 2018, the agricultural sector will be hit hard, requiring subsidies from the federal government. Revenues from tariffs will need to be diverted to help US farmers.

- Manufacturing/Industrial Markets. The largest beneficiaries of current tariff proposals are primary steel and aluminum manufacturing producers and raw material processors, while the industries hurt most would be those in the steel and aluminum supply chain – i.e., firms specializing manufacturing of steel and aluminum products, petroleum and coal products, and pharmaceutical products, all of which would face significant increases in input costs, resulting in potential lower exports and loss of employment.

- Deregulation | Banking & Credit Markets. Trump’s DOGE movement is focused on deregulating the US economy to free up resources for innovation and global competition. With respect to financial markets, if Trump decides to abandon the Basel III regime, as part of this DOGE/deregulatory movement, that could release over $3 trillion of reserves for deployment into the US economy. Given the impact of volatility on interest rates, we believe private credit is in the second or third inning of a nine-inning game with potential for overtime.

- Commodities | Precious Metals & Energy. Borrowing from Charles Dickens, the Commodity sector is truly “a tale of two cities”. For reasons we state throughout this paper, we are very bullish on gold. Gold and precious metals markets are truly in a perfect storm for more upside. For energy, while we are constructive on energy and specific sub-markets within energy, we could see softness in oil if the global economy softens with the onslaught of US tariffs and retaliatory tariffs from the rest of the world, throwing us back to the 1930s. As such, energy markets have to be navigated closely and investments made very selectively.

-

Introduction

This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of tariffs, exploring their historical context, track record, advantages and disadvantages, and more effective alternative policy measures.

First, President Donald Trump has positioned tariffs as a strategic tool for both domestic economic policy and national security. He argues that tariffs serve multiple objectives, including a) increasing national revenues, b) lowering trade deficits with countries (i.e., China), c) enhancing US leverage in international relations, d) protecting US borders from illegal immigrants and drug trafficking, and e) reducing dependence on foreign countries for critical industries and reliance on supply chains. In a recent television interview, Trump emphasized that tariffs could expand domestic manufacturing while serving as a bargaining chip in diplomatic negotiations.

To understand tariffs within a broader geopolitical framework, we must revisit the post-World War II period and the establishment of the Bretton Woods system. Over the past eight decades, the US has led the creation of an international economic order based on rules, laws, norms, and values that have arguably produced the longest period of peace in great power politics, and global prosperity unmatched in human history.

The US has fostered a network of powerful international alliances that provide multiplier effects on American influence across the entire world. In this international liberal order, the US has been the largest beneficiary, despite bearing significant costs, including maintaining the US dollar as the global reserve currency and setting geopolitical and geo-economic policy. This leadership has allowed the US to set the global economic and technological agenda, even with the concomitant rise of China and the Middle Powers.

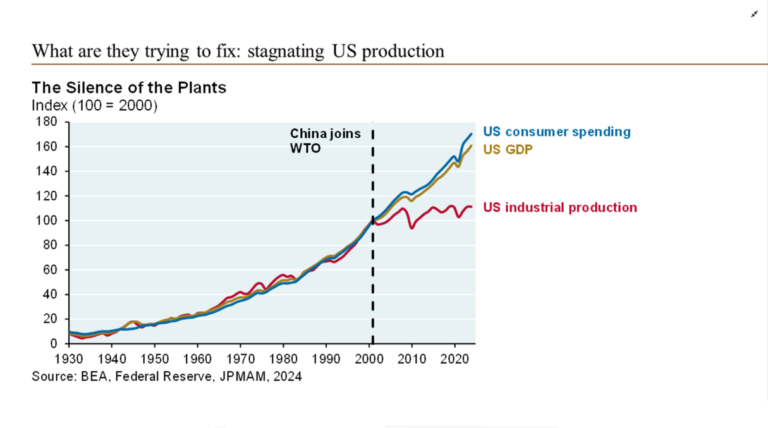

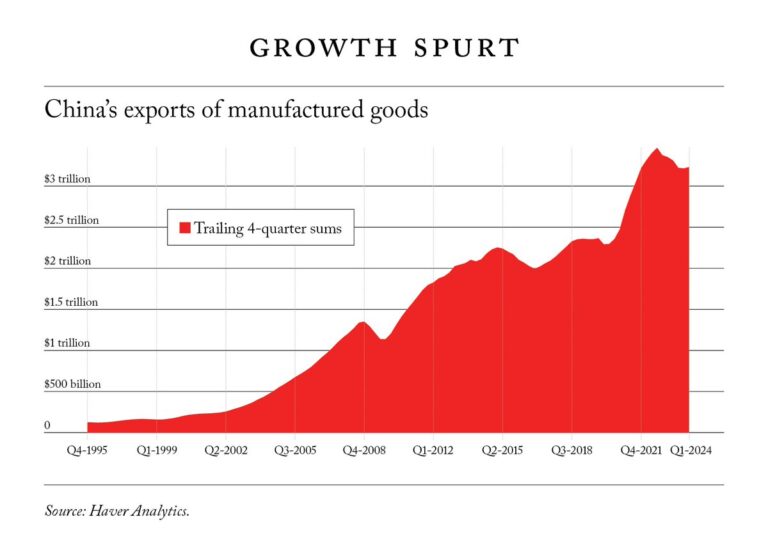

The globalization movement of the 1980s and 1990s further transformed the world economy, reducing poverty and fostering a global middle class, particularly in developing nations such as China and India, opening their economies to foreign trade and investment, contributing to rapid economic growth and creating a global middle class and the rise of the Middle Powers. One of the most important watershed developments of the 21st century will be the allowance of unfettered access of China into the WTO. From the illustration below, we can see that, since that time, US industrial production vis-à-vis US GDP has consistently flatlined, raising current national security concerns.

However, recent shifts in US trade policy, including the aggressive use of tariffs, threaten to unravel this carefully constructed international framework. As the US moves away from multilateral cooperation and toward unilateral economic measures, it risks weakening its global influence, destabilizing international alliances, and undermining the rules-based order that has historically benefited American economic and geopolitical interests.

Economic considerations have increasingly influenced national security policy, especially as China’s economic rise has positioned it as both a competitor and a national security concern for the US. The decline of domestic manufacturing, coupled with crises that have disrupted global supply chains, has prompted US policymakers to reconsider the wisdom of hyper-globalization and unregulated free trade as described in economic textbooks. The COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted the vulnerabilities of global supply chains, making economic resilience a core national security priority. Within his context, tariffs have now become the popular go-to weapon for the Trump administration to help turn the unfettered globalization tide.

The US government is now at a crossroads in determining how best to integrate economic policy into national security strategy. Two primary schools of thought have emerged:

- Government Support for Industry: This approach, favored by Democrats, advocates for subsidies and targeted government investments, as seen in the CHIPS Act. It also emphasizes strengthening global alliances and coordinating economic policies with strategic partners.

- Protectionist Measures: Led by Trump and many Republicans, this approach relies on adversarial and coercive tactics, including tariffs, to reduce foreign competition, boost domestic production, and protect industries vital to national security.

While both sides acknowledge the role of economics in national security, the debate centers on the effectiveness and consequences of these policy tools. Tariffs, in particular, have sparked intense discussion regarding their long-term impact and potential unintended consequences.

A nuanced analysis of tariffs requires examining empirical evidence to determine when and how they work. While tariffs can provide short-term benefits, such as protecting domestic industries, they also come with significant risks and long term implications, including higher consumer prices, economic distortions, retaliatory measures from trading partners, and reduced global competitiveness. Policymakers must weigh these factors against alternative strategies that could achieve similar objectives with fewer negative externalities.

Given the shifting landscape of trade policy and national security, investors must consider how tariffs, economic policy shifts, and the changing international order could impact financial markets and investment portfolios. Understanding these dynamics can help investors identify opportunities amid volatility and uncertainty.

The protectionist policies of recent years represent a significant departure from the long-standing international economic order. While the integration of economic policy into national security is a necessary evolution, the choice of policy instruments and implementation will determine the effectiveness and stability of this approach. A balanced strategy that strengthens domestic industries while maintaining international cooperation may offer the most sustainable path forward. As the debate over tariffs continues, a data-driven, pragmatic approach will be essential in crafting policies that protect national interests without sacrificing economic prosperity and the international alliances that the US has built.

Tariffs Defined & Historical Framework

Simply put, tariffs are taxes imposed by a government on imported goods. Stated differently, they act simply as a sales tax on imports. They come in various forms, including ad valorem tariffs (percentage-based), specific tariffs (fixed amount per unit), and compound tariffs (a combination of both). They are paid by domestic importers and not by foreign companies. As such, they inherently increase costs for domestic consumers and/or domestic producers. These types of taxes are also very regressive – i.e., they disproportionally impact lower and middle class households.

If these taxes are passed onto the consumer, the consumer will either purchase less or go with a cheaper substitute, preferably a domestically produced good. If importers and producers decide to lower prices to remain competitive, their lower revenues will either come from lower investment/capex spending, lower wages to employees, or lower profits to owners/shareholders. In essence, tariffs transfer income from consumers (net importers) to producers (net exporters) by raising the price of imported goods, ceteris paribus. We have to remember that the more revenues from domestic tariffs raise, the greater the costs on consumers.

They serve multiple purposes, including protecting domestic industries from foreign competition, generating revenue for the government, and influencing trade policies. By increasing the cost of imported goods, tariffs can make domestic products more competitive in the local market.

The use of tariffs dates back to ancient times, with significant developments occurring throughout history. In the 18th and 19th centuries, tariffs were primarily used to protect nascent industries in developing economies. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 in the United States marked a significant milestone, as it raised US tariffs to historically high levels, contributing to global trade tensions and retaliations, during the Great Depression. Post-World War II, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its successor, the World Trade Organization (WTO), aimed to reduce tariffs and promote free trade and liberalization globally. As tariff rates and transportation costs plummeted, international trade and globalization skyrocketed, increasing the general wealth of nations.

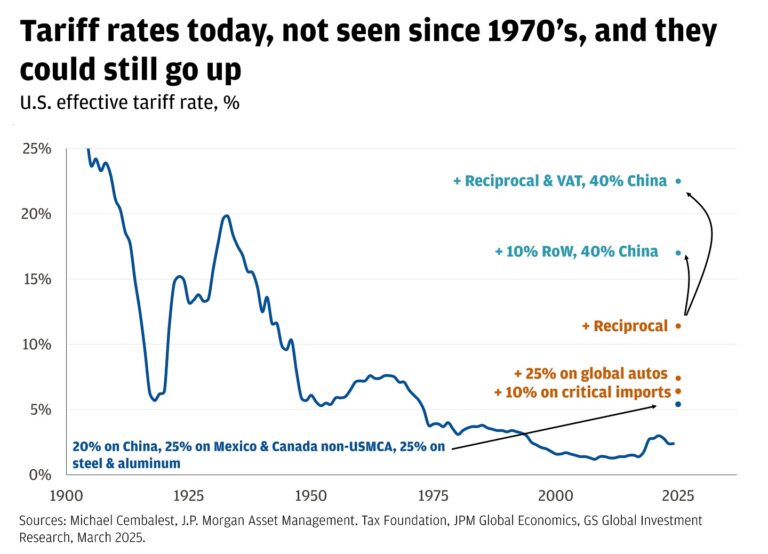

Fast forward to the 21st century, and we are seeing protectionism re-emerge as globalization is seen as the primary reason for the loss of the US manufacturing base. As a result, we are seeing Trump raise tariff rates not experienced since World War II. For example, if passed, average tariffs under Trump will increase from 7.4% to 17.3%, reaching levels not breached in over 70 years. Moreover, tariffs today will impact a larger component of the US economy due to proliferation of supply chains, global production networks, and the higher level of trade today, making them more disruptive.

While globalization and free trade agreements in the late 20th century lowered tariffs, we are now experiencing economic nationalism and the attractiveness of tariffs by those willing to use leverage for national interests. At these levels, we are seeing a tectonic shift from free market economics to one of protectionism and mercantilism. The use of tariffs as a protectionist tool is a misguided interpretation of economic history which could result in negative externalities to the US and our long-standing alliances.

Tariffs & the Legacy of President McKinley in Trump’s Economic Policy

Tariffs are at the core of former President Donald Trump’s admiration for President William McKinley. Tariffs as a cornerstone economic policy defined McKinley’s political career, with his final act as a congressman being the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890, which set the average tariff on dutiable imports at around 50%. For most of his professional life, McKinley conceptualized American power and security as functions of the country’s domestic economic well-being rather than the size of its military or its international relations. He strongly believed that broad-based tariffs, applied to thousands of tradeable goods, would help US industries grow and protect American workers.

Some critics argue that Trump’s historical comparison overlooks the failure of McKinley’s policies. For instance, McKinley’s eponymous 1890 tariff preceded a Democratic wave in the 1890 midterm elections as McKinley himself was voted out of office and his tariffs were eventually replaced by a federal income tax.

However, the problem is that McKinley’s tariff approach in the 1890s is not analogous to today’s globally intricate world. Whereas McKinley used tariffs primarily to accomplish a domestic goal of expanding US industry, Trump’s primary goal is external, at least based on his claims. His objective is to change the behavior of other countries, relying on the threat of broad tariffs to bring them to the negotiating table and extract concessions in areas of disagreement well beyond tradeable goods. Given his transactional approach, Trump measures and flaunts his success not by quantifying tariffs’ effects on US economic variables but by whether allies and adversaries capitulate to his demands, even if they are small “wins”. We would argue that Trump has McKinley’s model but in reverse.

Trump argues that tariffs produced American wealth in the industrial age, and McKinley believed the same, as experts have long been skeptical of that claim. Economic historian and tariff specialist, Douglas Irwin, argues that McKinley’s tariffs had a neutral effect, neither significantly helping nor significantly harming the overall US economy. However, history is unlikely to repeat itself in the same way under current conditions. Implementing the tariffs Trump has suggested in today’s world, with its modern, interconnected economy, would likely harm the US, at least by the reactions and counter-threats we have seen to date.

Moreover, other countries play a crucial role in determining the consequences of tariffs – i.e., as we have seen with retaliatory tariffs discussed above. If they do not retaliate immediately with tariffs of their own or some other escalatory response, they will likely do so over time. The more the US threatens, the more other countries will perceive it as a threat and seek to balance against it. The system of alliances and institutions the US has built and fostered since World War II and the soft power the US enjoys could erode. If Washington antagonizes its partners indiscriminately, they may start seeking alternatives, forming alliances with other countries to work against the US. Multilateral coordination on sanctions, export controls, trade agreements, intelligence sharing, and support for US military campaigns could all begin to unravel.

In conclusion, while Trump draws inspiration from McKinley’s economic policies, the world has changed significantly since the late 19th century. The US did not have a federal income tax in place, so tariffs were major revenue contributors. McKinley’s tariffs were designed to strengthen domestic industry, whereas Trump’s approach seeks to exert pressure on foreign governments in the name of national security. This fundamental difference, along with the realities of globalization and international economic interdependence, suggests that a protectionist tariff policy in today’s world could ultimately weaken US economic and geopolitical standing rather than strengthen it. This is our primary concern with this foreign policy in today’s very fragile world.

The Case for Tariffs as an Effective Policy Tool

While most economists argue against the use of universal tariffs as an effective economic policy, proponents contend that tariffs can serve as a powerful tool to advance a nation’s strategic interests. Advocates argue that tariffs can increase government revenues, protect domestic industries and jobs, reduce trade deficits, and safeguard national security. Although tariffs often spark debate over their economic efficiency, their targeted application, when combined with complementary policies, can support long-term economic stability and national resilience.

Increasing Government Revenues and Shifting Costs to Foreign Producers

One of the fundamental arguments for tariffs is their potential to generate government revenue while shifting the burden onto foreign producers. If foreign manufacturers absorb the cost of tariffs to maintain market share, domestic consumers may see little price impact, making tariffs an effective means of raising government funds without harming local purchasing power. However, this scenario depends on the price sensitivity of consumers – if consumers are relatively indifferent to price changes, foreign producers may not feel compelled to absorb tariff costs, and domestic buyers ultimately bear the financial burden. Despite this complexity, governments can leverage tariff revenues to subsidize affected industries and workers, mitigating potential economic downsides, particularly if other countries respond with retaliatory tariffs, which is often the case.

Protection and Revitalization of Domestic Industries and Jobs

Tariffs can serve as a buffer against foreign competition, allowing domestic industries to develop and sustain employment. When properly implemented, tariffs can encourage local production by making imports more expensive, thereby giving domestic manufacturers a competitive edge. This is particularly relevant for revitalizing key industries that have declined due to outsourcing and international cost advantages. Additionally, targeted tariffs can be appropriate in certain circumstances, such as countervailing duties against trading partners’ subsidies to give domestic industries time to adjust.

However, the long-term success of such measures depends on parallel investments in workforce development, manufacturing innovation, and infrastructure. Without these supporting elements, tariffs risk shielding inefficient industries at the expense of broader economic progress.

However, one of the fundamental misconceptions about tariffs is that they will lead to a significant increase in factory jobs. While tariffs function as a form of subsidy for domestic production, they do not necessarily translate into increased employment. Modern manufacturing is increasingly reliant on automation, robotics, and advanced technology, reducing the need for human labor. As a result, while tariffs may encourage companies to establish production plants in the US, they do not guarantee the large-scale job creation that might have been expected in previous decades.

Moreover, tariffs act as a tax on consumption, increasing prices for households on final goods. This effect is even more pronounced in industries that rely on intermediate inputs such as steel and aluminum. By making these essential materials more expensive, tariffs can hinder job creation in downstream industries. Rather than boosting overall employment, they often result in a redistribution of jobs between industries, sometimes at a net loss. For example, economists estimate that for every job created in a US steel mill due to tariffs, 80 workers in industries reliant on steel – such as automobile manufacturing, machinery production, and farm equipment – face negative consequences. Companies in these sectors struggle to compete with foreign rivals that have access to cheaper raw materials and cheaper labor.

Challenges Posed by Retaliatory Tariffs and Currency Adjustments

One major concern surrounding tariffs is the potential for retaliatory measures from trading partners, which can neutralize their intended benefits. For example, retaliatory tariffs on US exports can lead to job losses in affected sectors, as was observed following the steel tariffs imposed in 2018. Additionally, tariffs can trigger currency adjustments in global markets, wherein exchange rates shift to balance trade flows. Such adjustments may buffer price increases for domestic consumers but can simultaneously harm exporters, reducing their competitiveness in global markets. Consequently, tariffs function as a wealth transfer from domestic importers to exporters, rather than a straightforward mechanism for economic protection.

The Limitations of Tariffs in Reducing Trade Deficits

Trade deficits are complex phenomena influenced by macroeconomic factors, including national savings rates, capital inflows, and currency valuations. The United States, for example, has maintained prolonged trade deficits due to its low domestic savings rate and high foreign investment inflows, which reflect the nation’s attractive investment climate. Given these structural factors, tariffs alone are insufficient to address trade imbalances. Instead, effective solutions require broader economic policy adjustments, such as encouraging domestic savings, reforming tax policies to reduce excessive capital inflows, and negotiating fair trade agreements that promote balanced economic relationships.

Addressing the Role of China and the Global Trade Landscape

China’s persistent trade surpluses are largely the result of government policies that suppress wages and encourage savings, making Chinese exports highly competitive. In contrast, the US tax and financial system incentivizes consumption and borrowing over investment in domestic production. Thus, addressing trade imbalances requires policy shifts that encourage domestic manufacturing investment and worker training rather than solely relying on tariffs.

Moreover, while the Trump administration’s tariffs led to a decline in direct US-China trade, global supply chains have adjusted, with intermediate manufacturing hubs such as Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and Mexico playing greater roles in rerouting Chinese-made inputs to US markets. This underscores the need for a strategic approach beyond simple tariff imposition. For example, one alternative may include coordinating with strategic trading partners like the European Union, the UK, and Australia on a carbon tax to address China’s heavily subsidized manufacturing and overcapacity sectors such as electric cars, batteries, photovoltaics, etc.

Source: Hoover Institute, Council of Foreign Affairs

A Strategic Approach to Strengthening Domestic Industry & Manufacturing | Alternatives to Tariffs

To truly enhance domestic manufacturing and economic competitiveness, tariffs must be harmonized with broader policy initiatives. A more effective approach to reducing trade imbalances and revitalizing industries includes:

- Increasing Domestic Savings: Encouraging investment in manufacturing and infrastructure to reduce reliance on foreign capital.

- Smart Immigration Policies: Addressing labor shortages through targeted immigration strategies that align with workforce needs.

- Tax and Investment Reforms: Reducing excessive capital inflows that contribute to trade deficits while incentivizing domestic production.

- Negotiating Fair Trade Agreements: Ensuring that US trade deals promote long-term economic stability while countering unfair practices.

- Coordinating Currency Policies: Engaging with major trade partners, such as China, Japan, and Germany, to achieve balanced exchange rates.

- Government Support for Key Industries: Strategic investments in sectors vital for economic and national security such as semiconductors, and industries supporting national defense.

National Security Considerations

Beyond economic arguments, tariffs can be justified on national security grounds. The reliance on foreign suppliers for critical industries – such as semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, and defense-related manufacturing – poses strategic risks. From the illustration below, we can see how entrenched Chinese supply chain is with our defense spending and overall defense industry. As such, the government has proactively stepped in and created incentive programs to foster innovation. A number of private equity firms, in coordination with government agency, are providing debt and equity capital to facilitate the growth of these types of firms focused on national security. This is one example of addressing global supply chains not involving protectionism and tariffs.

In cases where national security is a priority, targeted tariffs, combined with government support for domestic production, can ensure a stable supply of essential goods. While broad-based tariffs may be economically inefficient, selective measures aimed at reducing dependence on authoritarian regimes or unstable supply chains can be a rational policy choice.

However, instead of relying on tariffs alone, more effective industrial policies can be implemented to strengthen key sectors without imposing heavy costs on consumers and businesses. A more strategic approach includes targeted subsidies, such as the CHIPS Act, which aims to diversify the US technology supply chain while minimizing economic disruptions. Unlike tariffs, these policies provide direct financial incentives for domestic production while maintaining cost-efficiency for industries reliant on critical components. Although industrial policy requires the government to play a role in selecting strategic industries, it can be a more constructive approach than broad-based tariffs.

Furthermore, cooperation with allies offers a viable alternative to unilateral tariff policies. The Biden administration has emphasized working with international partners to build resilient supply chains outside of China. This includes co-financing semiconductor fabrication facilities in Germany, Japan, and the United States, as well as the development of the Minerals Security Partnership to coordinate investment in mining and processing of critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, and graphite.

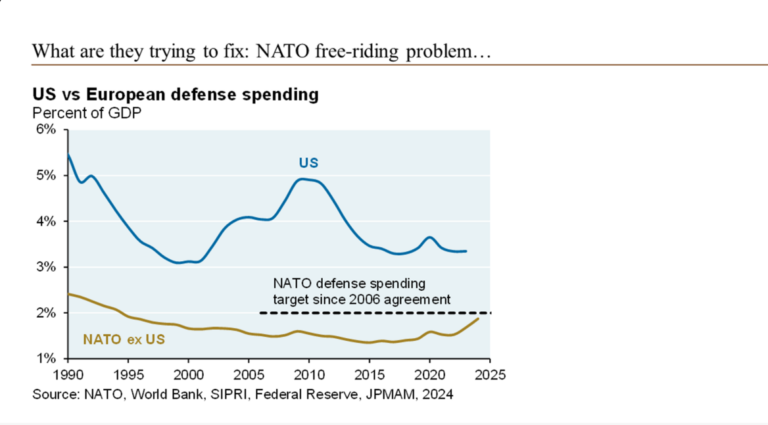

These collaborative efforts help spread costs, mitigate risks, and enhance economic security without introducing trade distortions. In contrast, Trump has shown little willingness to engage in such cooperative industrial policies and has even called for the repeal of the CHIPS Act. Additionally, our NATO partners agreed in 2006 to raise spending across the membership to at least 2% of their GDP. While it took them over 15 years, they are there and some are planning on spending more, which should relieve the US from that treaty obligation.

While tariffs alone cannot solve all economic challenges, they remain one viable policy tool when strategically implemented alongside broader economic reforms and other public and private sector initiatives. Effective tariff policies should be precise and accompanied by investments in domestic industries, labor force development, and diplomatic trade negotiations. When used as part of a comprehensive economic strategy, tariffs can protect key industries, generate revenue, and strengthen national security without unduly harming consumers or broader economic growth. Ultimately, a well-balanced approach that incorporates tariffs selectively, rather than universally, offers the best path toward national security and sustainable economic resilience.

Trade Surpluses – Impact of Tariffs On China & US

A Quick Primer on the Bretton Woods System & Trade Imbalances

Based on the Bretton Woods financial architecture, serving as foundational player of the global economy, the US must allow capital to flow freely across its borders and absorb the excess savings and production of other nations – i.e., China. This means the US runs trade and capital account deficits, enabling surplus countries to convert their excess output into US assets – i.e., real estate, stocks, bonds, Treasuries, and factories. While this system defines the dollar’s global dominance, it also creates structural pressures on the US economy, often manifesting as higher fiscal and consumer debts, or high levels of domestic unemployment.

Global imbalances today are constrained not by trade policy or gold convertibility, but by the US’ willingness and ability to act as the consumer of last resort, as well as the global recipient for foreign surplus capital. This allows other countries to run persistent surpluses or deficits, with the US running opposite imbalances by importing capital and exporting claims on domestic assets.

Further, these deficits are not counterbalanced by expansion in surplus economies. In the post-World War II Bretton Woods negotiations, economist John Maynard Keynes warned against a system that allowed persistent imbalances without forcing surplus countries to adjust. However, he was opposed and overruled by US Treasury official Harry Dexter White, resulting in a global order where adjustment burdens fall disproportionately on deficit countries, such as the US.

Surplus economies, such as China, Germany, or Japan, do not run surpluses solely because of manufacturing efficiency. Their surpluses are often supported by a combination of implicit subsidies (especially in China), export-driven industrial policies, and the suppression of domestic consumption through a variety of legislative mechanisms – the hallmarks of a mercantilist system. These surpluses come at the expense of domestic households and workers.

Looking at empirical evidence, from the 1920s through the 1970s, the US played this role, providing the capital needed to reconstruct war-torn regions in Europe and Asia. During this era, the US was the world’s preeminent surplus nation and creditor, running large current account surpluses.

Since the 1970s and 1980s, global economic conditions had changed. After countries were rebuilt, these economies matured and looked to export their excess capital, the US pivoted, remaining open at that point to a flood of foreign capital. Its open, liquid, and well-regulated financial markets allowed it to absorb the world’s surplus savings. Not coincidentally, this was the period during which the US trade surplus eroded and transitioned into the persistent deficits we observe today.

No other country has taken on this role at such scale, which is why no other currency rivals the dollar in international trade and finance. Moreover, no major economy appears willing or capable of doing so. China, the EU, and other Asian countries maintain capital controls, rely heavily on exports, and would require profound domestic and institutional reforms, such as redistributing income from businesses and national champions, liberalizing capital markets, and tolerating greater imports and debts to assume the US position as the linchpin of the global trading system.

We can’t lose sight that the dollar remains irreplaceable not simply because of US economic size, but because of the institutional and structural role the US plays in global finance that comes at a deep cost. Should the dollar lose this role, the current global economic order would quickly unravel. If the US ceased absorbing the world’s excess savings and production, surplus countries would be forced to cut output or stimulate domestic demand. Without the dollar as the global trading fuel, the trade surpluses that have fueled growth in countries like China, would no longer be sustainable.

In short, the dollar’s central role has enabled the large global imbalances of the past half-century. No other country has both the institutional flexibility, transparent legal system, and political willingness/ability to step into this role. Until that changes, the dollar’s dominance will remain firmly entrenched. And the US’ “exorbitant privilege” continues.

Trade Surpluses & China

One of the primary reasons why tariffs are being discussed and implemented by this and the previous administration has been to reduce trade surplus that other countries have with the US. And for reasons we discussed earlier, the primary country where trade surpluses have become an issue is China. We provide a brief description of the problem of trade imbalances and how tariffs impact these imbalances.

China’s economic growth model, used over the past four decades, has been primarily driven by investment rather than consumption, which has led to significant trade surpluses, and arguably decades of low interest rates in the US. Understanding the relationship between investment and trade balances provides insight into both China’s economic structure and the potential effects of current tariff policies. This can also help us with ascertaining the probability of inflation and direction of interest rates over the long term.

China’s rapid economic expansion has been fueled by high levels of investment in infrastructure, manufacturing, and other productive capacities. As of December 2023, China’s private consumption accounted for 39.6% of its nominal GDP, up from 37.8% in 2022. This marks an increase from the record low of 34.9% in 2010. On a relative basis, this ratio remains very low compared to developed countries, where household consumption typically comprises 60-70% of GDP, as is the case in the US and other developed countries.

This emphasis on investment has significantly increased China’s production capacity, leading to an oversupply of goods. Since domestic consumption remains low, the surplus goods are exported, contributing to persistent trade surpluses. Within the Bretton Woods System and the dollar’s role within that system, these surpluses have mainly hit US shores, although China has made a concerted effort to diversify its export markets, primarily with mechanisms such as the Belt & Road Initiative.

Countries with large current account and trade surpluses, like China, must invest their excess savings in foreign assets. The US, with its liquid, transparent, deep, and open financial markets, serves as a natural destination for these investments. This dynamic inherently results in the US running a corresponding current account deficit. However, projections of long-term consumption growth in China remain uncertain due to the political challenges of structural reforms aimed at redistributing income from business and government to consumers.

China’s investment-driven economy has strengthened its position as a major exporter of investment goods, such as bulldozers, forklifts, telecom equipment, and since 2016, electric vehicles, photovoltaics, and batteries. The contribution of capital equipment to export growth has doubled, further widening trade surpluses. Additionally, China has actively intervened in its currency markets to keep the RMB undervalued, making Chinese goods cheaper internationally and enhancing export competitiveness. This deliberate currency manipulation, in addition to its arcane growth model, has been a key factor in sustaining China’s trade surpluses.

A major characteristic of China’s economy is its low household consumption relative to GDP. With consumption intentionally suppressed, this structural imbalance means that a substantial portion of the goods produced in China must be exported rather than consumed domestically, reinforcing trade surpluses. Until significant structural, political, and institutional reforms are implemented to boost domestic consumption, China’s economy will remain heavily dependent on exports and investment, focusing on trade surpluses, despite what the US does with tariffs.

In contrast, the US, as the reserve currency and as the global consumer under a Bretton Woods framework, maintains a high level of consumption and a significant trade deficit, meaning that Americans consume more than they produce, for reasons that are not necessarily domestic in nature.

To correct these imbalances, tools are needed that attack the core of the problem – i.e. the Chinese economic growth model and underconsumption of the Chinese consumer. Some economists argue that properly implemented tariffs could redirect US demand towards domestic production, increasing GDP, employment, and wages while reducing national debt. However, the goal should not be to protect specific industries but rather to address the broader issue of the US’ pro-consumption and anti-production economic structure.

Some economists further note that tariffs could pressure China’s GDP growth and potentially encourage a shift in China’s economic model from investment-driven trade surpluses to increased domestic consumption. They argue that higher tariffs on Chinese goods could accelerate this transition by limiting export opportunities. Even since Wen Jiabao’s famous 2007 speech where he recognized for the first time the underconsumption problem and promised change, we see no evidence of this much-needed shift.

However, we would challenge this tariff assumption, emphasizing that trade imbalances are intrinsically linked to internal economic imbalances. Xi Jinping has done little in the way of institutional reforms to help alleviate these imbalances. On the contrary, Xi’s laser focus in 2016 on higher-end manufacturing – i.e., electric vehicles, photovoltaics, semi-conductors, batteries, and other high-end goods – indicates his proclivity to export more. China now has the capacity to produce almost 50% of the annual demand for new automobiles, yet they are at 60% capacity, indicating further room for growing auto exports of Chinese vehicles, including Teslas. What about all their other products?

Tariffs are often perceived as a straightforward tax on consumption that disproportionately harms consumers. While it is true that tariffs increase the cost of imported goods, they may theoretically serve to benefit domestic production at the expense of imports – hence, Trump’s focus on high, broad-based tariffs as a policy tool. If tariff policies successfully stimulate domestic production to the extent that they increase overall consumption, they can ultimately improve economic conditions.

However, the effectiveness of tariffs in reducing the US trade deficit assumes a) other countries do not impose significant retaliatory tariffs – a fact that we know is false from empirical evidence, b) consumers will not decide to purchase more foreign goods, and/or c) no other unpredictable market disruptions. If major trading partners respond with countermeasures, the intended benefits of tariffs may be quickly undermined, leading to broader economic disruptions and quickly defeating the original objectives of tariffs.

China’s investment-driven economy has resulted in high trade surpluses due to low domestic consumption and strong export growth, for reasons we explained above. While tariffs imposed by the US could potentially alter this dynamic, their ultimate impact remains uncertain and highly dependent on broader economic conditions and policy responses. The challenge for policymakers is to balance trade policies in a way that fosters economic stability, encourages domestic production, and promotes sustainable long-term growth. Understanding the systemic nature of trade imbalances is essential in shaping effective economic strategies for both China and the US.

In sum, tariffs alone are not the elixir to eradicating trade surpluses, and in some situations, can worsen surpluses. In 2024, the US ran trade surpluses with 111 countries, including Singapore, UK, and several South American countries. Are we exploiting these countries? Do the US trade surpluses justify those countries placing tariffs on our goods?

The problem is that the solution to trade imbalances is costly and disruptive. If the US decides to stop absorbing excess global/Chinese savings and running persistent trade deficits, China and other trade surplus countries will have to dramatically downsize entire industries that are currently geared for major exports, such as China’s automotive industry. The transition will entail more than potentially selecting a new currency in which to transact. It will involve building radically different frameworks and systems for trade and capital flows. And while these may be more sustainable and beneficial to the US economy in the long run, their adoption will be messy and painful for the world’s surplus economies. Only globally coordinated efforts will even make this transition possible.

The Geopolitical and Economic Implications of Tariffs

Tariffs can serve as both economic instruments and geopolitical tools, significantly influencing international relations and trade balances. While they can exert pressure on other nations to achieve strategic goals, albeit with mixed results, they can also escalate tensions, disrupt major alliances, damage institutional norms, and fail to address fundamental macroeconomic factors driving trade deficits/surpluses.

Tariffs are often used as leverage to influence the economic and political decisions of other countries – i.e., consumption/manufacturing/exporting patterns, immigration, drug trafficking and other political issues. Governments may use tariffs to pressure countries into adopting more favorable policies regarding human rights, environmental standards (i.e., carbon tariffs), immigration, or trade practices. However, this approach can lead to strained diplomatic relations and even economic retaliation, further exacerbating international tensions and delicate strategic alliances. Conversely, the reduction or elimination of tariffs can foster improved trade relationships and economic partnerships.

Despite their intended goals, tariffs do a poor job at addressing the underlying macroeconomic factors that drive trade deficits. A country’s trade balance is fundamentally determined by the relationship between national savings and investment. For instance, the US, with its historically low savings rate and high investment rate, consistently runs a trade deficit. When Americans purchase foreign goods, the dollars earned by foreign exporters often return to the US in the form of capital investments in stocks, bonds (Treasuries), and real estate rather than purchases of US-made goods.

If policymakers truly aimed to reduce the trade deficit, they would be better served by addressing fiscal policies that contribute to excess spending in some countries, and excess savings/low consumption in others. For example, reducing the federal budget deficit could lower the need for foreign capital inflows, thus narrowing the trade deficit. Additionally, reforming the US tax code to a) incentivize savings rather than consumption and b) disincentivize foreign investments in the US could also help rebalance trade flows.

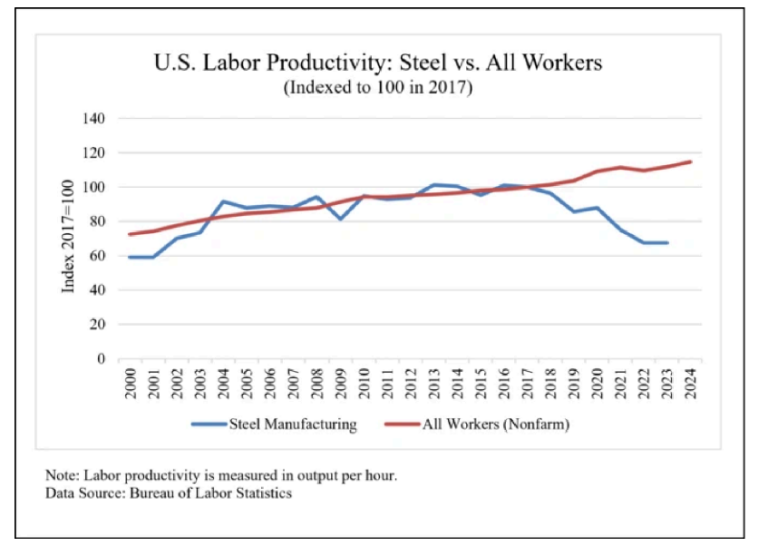

With that said, the protectionist tariff policies implemented over the past eight years by both Trump and Biden have largely failed to achieve their objectives. The push to revive manufacturing employment overlooks a broader historical trend – i.e., the declining share of manufacturing jobs due to technological advancements. As productivity increases, fewer workers are needed to produce the same output, allowing wages and living standards to rise. Rolling back these advancements would be counterproductive to economic progress. While tariffs may protect manufacturing, it does not necessarily boost manufacturing employment.

Further, empirical studies have shown that import tariffs often depress labor productivity in the industries they are intended to protect. This occurs because protectionist policies could impact the following:

- Allow less competitive firms to survive by shielding them from global competition.

- Reduce the incentive for domestic companies to invest in innovation and efficiency improvements.

- Diminish collaboration and knowledge-sharing with foreign firms, stifling technological advancements.

A clear example of this is the US steel industry following the imposition of 25% tariffs on steel imports in March 2018. Since then, output per hour in the US steel industry has declined by 35%, while productivity across the broader economy has increased by 15%. Moreover, US steel-consuming firms, which employ 45 times more workers than steel producers, now pay approximately 75% more for steel compared to their foreign competitors. This cost increase hampers US competitiveness and negatively impacts American workers and American standards of living.

The protectionist policies pursued by the Trump and Biden administrations have not only failed to reduce the trade deficit but have also led to unintended economic consequences – trade tensions and retaliatory tariffs. Tariffs do not address the core structural issues of trade imbalances, and their use as a geopolitical tool often leads to more harm than benefit. Rather than resorting to protectionism, policymakers should focus on increasing national savings, reducing fiscal deficits, and fostering productivity-enhancing policies, which are much harder to implement than imposing a tariff. By embracing free trade and market-driven industrial policies, the US can achieve sustainable economic growth while maintaining its competitive edge on the global stage and not deteriorating its soft power with deleterious tariffs that fail to achieve their objectives.

Trump/Biden Tariffs – Empirical Observations – A Case for Strategic Economic Policies & Free Trade

Trump (and Biden’s) protectionist trade policies starting in 2018 were intended to a) strengthen domestic industries (and employment) and reduce trade imbalances, particularly with China. However, empirical evidence suggests otherwise – instead of revitalizing US manufacturing, reducing the Chinese trade deficit, and geo-strategically decoupling from China, these measures have exacerbated the underlying symptoms, raised consumer costs, and in Trump’s current case, are drastically weakening international cooperation and jeopardizing the US’ soft power built over the past eight decades.

Alternatively, we would argue that free trade, coupled with a market-driven approach to industrial policy, in close coordination with our alliances, offers a more effective path forward for economic growth, national security, and global order.

Protectionist policies have not yielded the anticipated benefits for US manufacturing employment, trade balance, or economic independence/decoupling from China as was touted by politicians.

- Manufacturing vs. Manufacturing Employment: Contrary to expectations, tariffs and trade restrictions have not led to a resurgence in manufacturing jobs. Instead, they have contributed to job losses through a second derivative effect by increasing production costs (tariffs on imported intermediate goods raise production costs making US-based manufacturing less competitive, leading to manufacturing job loss) and prompting retaliatory tariffs from other countries, further reducing the competitiveness of US manufacturing.

- Trade Deficit: The overall trade deficit has not been reduced by protectionist policies; in fact, it grew materially during the Trump administration. This suggests that trade deficits may be driven by broader macroeconomic factors such as national savings and investment levels rather than trade policies alone – i.e., currency manipulation, emphasis on investment driven growth, low household consumption.

- Economic Decoupling from China: Despite tariffs and other restrictions, economic ties between the US and China remain strong. While a fulsome discussion of US-China relations is beyond the scope of this paper, since the initial Trump tariffs, the trade deficit has soared, particularly with China’s focus starting in 2016 on subsidizing electric vehicles, photovoltaics, batteries and rare earth metals. Additionally, businesses have found alternative ways to maintain trade relationships, demonstrating the limits of government intervention in global supply chains and how interconnected the world is.

For the reasons we have stated in this paper, the objectives underpinning protectionist tariff policies are based on flawed economic beliefs and assumptions, especially for those with a geopolitical underpinning.

- Manufacturing Employment: The decline in manufacturing employment is a far more complex topic, largely attributable to technological advancements, as well as other geopolitical factors, and not trade policy per se. For example, automation and productivity improvements have reduced the number of jobs needed in manufacturing, making protectionist efforts to restore past employment levels ineffective. While tariffs may initially benefit certain manufacturing industries, this may not translate into increased manufacturing employment.

- Trade Deficit: The persistence of the trade deficit highlights that it is primarily influenced by macroeconomic factors rather than trade policies. Efforts to eliminate it through tariffs and trade barriers overlook the fundamental drivers of global capital flows and the underlying dynamics and flaws with China’s economic growth strategy and lack of consumption and surplus of savings.

- Free Trade: The primary goal of free trade is not job creation but rather enhancing productivity, wages, consumer welfare, and overall national economic well-being. By leveraging and maximizing comparative advantage, free trade improves economic output and living standards, making economies more efficient and competitive.

Empirical studies and historical trends provide clear evidence of the negative consequences of protectionist policies. For example, studies show that the tariffs imposed during the Trump administration led to higher consumer prices, increased production costs, and a decline in manufacturing employment. Retaliatory tariffs from other countries further exacerbated these issues, harming US exporters and US consumer. Further, 95% of all revenues raised by Trump tariffs went to subsidize American farmers from the loss of revenues as a result of foreign retaliatory tariffs on US agricultural imports. The net result was failed objectives of tariffs that were paid for by American consumers.

Rather than broad protectionist measures such broad tariffs, the US should adopt a more targeted approach with tools designed for economic security.

- Surgical Focus: Government intervention should be limited to specific types of goods and technologies that are deemed critical for national security, rather than implementing broad tariffs that disrupt entire industries.

- Power of Alliances & Cooperation: Working with allies to diversify production and supply chains away from adversarial nations is a more effective strategy than unilateral protectionism, especially the use of protectionism against allies. Strengthening partnerships can mitigate economic vulnerabilities without isolating the US from global markets and the benefits of free trade and globalization.

- Productivity and Innovation: Policies should focus on enhancing productivity and innovation rather than imposing trade restrictions. Investments in workforce development, infrastructure, and research can create sustainable economic opportunities for American workers while not necessitating protectionist measures that might trigger retaliation.

To summarize, protectionist policies have not delivered their benefits because of their flawed reasoning. The continued use of tariffs under both Trump and Biden has not revitalized manufacturing employment, increased government revenues, reduced the trade deficit, or achieved economic decoupling from China. We would argue that trade interdependence with China has only worsened.

Instead, these measures have increased costs for domestic consumers, spurred retaliatory actions, and most importantly, weakened international alliances and the US’ soft power. A strategic approach to economic security, focused on targeted industrial policies, global alliance cooperation, and free trade, provides a more effective path to sustained growth and global competitiveness. The US must prioritize policies that enhance productivity, innovation, and market efficiency to ensure long-term economic prosperity and not short-term, unsustainable gains from protectionist strategies.

Case Study | Tariffs Imposed on Canada & Mexico

Several years ago, President Trump ushered in a new phase in the US – Canadian – Mexican relationship – the US – Mexico – Canada Agreement (USMCA). Trump described the agreement, which borrows heavily from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement with some modifications, as a “terrific” accord, despite already having a free trade agreement with those countries. In his second term, however, Trump once again has a new US-Canadian relationship in mind – outright acquisition as a 51st state. In fact, his direct statement was “Canada only works as a state.”

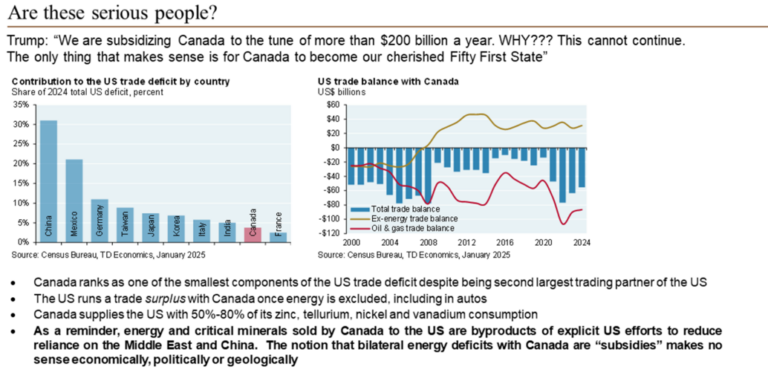

While such actions represent a stark departure from past presidential approaches to Canada, which ranks as one of the smallest components of the US trade deficit despite being the second largest trading partner with the US. Trump’s grievances about trade policies are not entirely without merit. Issues such as Canada’s subsidization of its lumber and protectionist dairy policies have long been points of contention between the two nations, although handled under the USMCA.

One of the most persistent disputes is the timber trade. The US – Canadian lumber industry has a history of tensions dating back two centuries, with the US claiming that Canada’s government-owned timberlands give Canadian producers an unfair advantage by allowing them to acquire logging concessions at artificially low prices. The Biden administration recently increased tariffs on Canadian softwood lumber, and Trump has pushed for further measures, including an executive order to expand US timber production for “national security” purposes.

The dairy industry represents another major source of contention. Canada’s dairy supply management system imposes steep tariffs on imports, creating what critics describe as a de facto monopoly that benefits domestic producers while limiting competition. Although USMCA allowed limited access for US dairy exports, Trump has argued that the system remains unfair to American farmers. However, US dairy exports have not yet exceeded the tariff-free quotas provided under USMCA, indicating very low negotiated tariffs on dairy products.

While Trump’s trade complaints may hold some validity, his recent tariffs against Canada appear to serve an alternative, broader strategic goal – forcing Canadian leaders into submission and signaling to other countries that he is willing to take extreme measures and not to call his bluff. However, this approach has provoked a strong populist and nationalist response in Canada, with growing public support for a “buy Canadian” movement, boycotting American products and the rise of new political leadership under Mark Carney. A recent poll indicated that 42% of Canadians are actively avoiding US products and traveling to the US and spending tourist dollars.

Despite Trump’s assertion that the US does not “need anything” from Canada, economic interdependence portraits a very different story. Canada is the largest supplier of heavy crude oil to US refineries, which are specifically retrofit to process it. In fact, energy and earth minerals exported from Canada are an intentional strategy to reduce reliance on the Middle East and China. If we remove energy from the equation, the US actually runs a trade surplus with Canada.

Canadian electricity exports play a crucial role in powering several US states, while Canada also provides significant quantities of critical minerals such as nickel and zinc. Fertilizer such as potash, essential for US agriculture, is another key resource predominantly sourced from Canada. If Canada does not supply vital fertilizer, its other sources include Russia, China or Belarus, making Canada a vital partner for food and energy security.

Beyond economics, Canada is a vital ally in security and intelligence. As discussed above, under NORAD, the two countries collaborate on defending North America from external threats. Canada has also supported US military efforts, notably in Afghanistan, where Canadian forces suffered significant casualties. Intelligence-sharing under the Five Eyes alliance (i.e., Canada, US, UK, Australia & New Zealand) remains critical for tracking military developments in adversary nations such as China and Russia.

The Trump administration briefly considered withdrawing from some of these joint security efforts but ultimately backed down, likely recognizing that such actions would harm US strategic interests. However, Trump’s aggressive trade policies have strained and tarnished Canadian perceptions of the US, with some polls indicating that a significant portion of Canadians now view the US, once a very close ally, as an “enemy country.”

As US – Canadian relations remain strained, the long-term implications of Trump’s novel approach remain unclear. Trump’s use of tariffs as a strategic weapon will not only directly increase costs for US consumers, but it will also provoke retaliatory tariffs that will hurt American exporters, It will further increase nationalistic political sentiment among other trading partners and incentivize other leaders to deploy tariffs and other trade restrictions. Regardless of the outcome, the current trajectory suggests a fundamental shift in North American economic and geopolitical dynamics.

The Power of Cross-Border Tax Policy

We would argue that changes to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) could be a more effective catalyst for directly incentivizing firms to hire more workers in manufacturing and other industries.

The IRC currently encourages offshoring by taxing foreign corporate income at a rate lower than domestic corporate income. For example, it is a well-known fact that large pharmaceutical companies pay little to no US income taxes simply by setting offshore subsidiaries and “patent boxes” to shelter income in lower tax haven jurisdictions. From the left illustration below, we see that over the last several years, US big pharma ran losses in the US while offshoring large profits to places like Ireland and Luxembourg. From the right illustration, we further can see that the US pharma trade deficit and offshoring tax shelter trends accelerated tremendously since the 2018 Tax Cuts & Jobs Act with the enactment of the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income regime, et al.

Additionally, based on current bilateral treaties, grounded on the IRC, the IRC favors investments by foreigners over those by American taxpayers. For example, a US tax resident receiving dividend income from a US company would pay tax of ~20%, whereas a Chinese sovereign wealth fund investing in the same US company would pay no US tax at all. A US resident receiving interest on a corporate bond or a Treasury security would pay tax at his/her marginal ordinary rate, which could be 37% or more. A Chinese sovereign wealth fund would pay nothing.

This income tax treaty dynamic significantly incentivizes Chinese nationals to invest in US assets. Partly for this reason, there is a massive imbalance in capital flows between China and the US. Concomitantly, the more attractive the after-tax returns on dollar investments are to Chinese entities, the more goods China can sell in the US to earn dollars.

Changing the IRC and bilateral treaties to make those investments less attractive would reduce the Chinese government’s incentive to subsidize the export of steel, batteries, electric vehicles andphotovoltaics. In 2024 alone, China’s goods-trade surplus with the US was over $295 bln – this recurring trade surplus may be much less if we stopped supporting it with huge tax breaks for Chinese investors.

Trump could also cut the payroll tax, which tends to discourage companies from hiring workers, for manufacturing firms. But any effort to revive US manufacturing jobs will face significant headwinds from other factors. For example, the share of workers in manufacturing is declining in most industrialized economies. As populations become wealthier, they can afford to spend more on services such as education, health care, and leisure provided locally. Job growth is likely to continue to shift away from manufacturing and toward those service sectors, with or without tariffs.

Since China’s ascension to the WTO in 2001, its economy has increased over 1,400% and its ability to dominate an industry is much easier – since 2016, China has become the dominant global powerhouse in EVs, photovoltaics, and batteries through huge government subsidies and predatory economic policies. To counter these mercantilist policies, we can revise the IRC and the US-China Tax Treaty would actually:

- Raise revenues from overseas actors, unlike tariffs

- Encourage more US investment at home.

Raising the US withholding tax on interest income could reduce Chinese investment in the US, leading to a reduced Chinese trade surplus, without imposing tariffs and associated externalities.

Reciprocal & Retaliatory Tariffs – Unintended Consequences

Because retaliatory tariffs are almost always the norm, especially if applied broadly to larger countries, it is critical for policymakers to understand the implications of such retaliatory tariffs when imposing tariffs to any one country. For example, many economists believe that other countries levy higher tariffs on US exports than the US levies on their goods, although not uniformly across all countries. The average tariff EU countries apply to US products is 5.0% which is close to the average US tariff on products from Europe of 3.4%.

There are several issues related to retaliatory and (Trump’s concern with) reciprocal tariff agreements:

- There are many countries with lower tariff rates than the US on certain goods (i.e., Japan on autos, Europe on trucks, New Zealand on dairy products). Will Trump offer to match those rates lower for the US?

- Even with countries where Trump negotiated reciprocal tariff agreements, Trump often threatens to extract more, often in non-tradable concessions. For example, the US had zero rate reciprocal tariff agreements with Canada and Mexico (NAFTA) but coerced them into signing the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) during his first term, only to threaten 25% tariffs on those same countries in his second term as punishment for their insufficient border security and enforcement against fentanyl trafficking. Not respecting existing agreements can have material negative implications in assuring an orderly international trading system.

- Trump threatened Colombia, with whom we have a zero rate reciprocal tariff agreement, with higher tariffs and a trade war because the president did not accept deportees en route to Colombia.

- When Trump pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017 because it was “unfair”, he gave away the ability to benefit from zero tariffs and reciprocity from trading partners such as Japan, Malaysia & Vietnam.

- In 2018, the US imposed tariffs on nearly all imports of steel, aluminum, and on a broad range of other products from China under domestic legal authorities (see further discussion below) to address national security concerns and China’s unfair theft of intellectual property and technology transfer policies. In response to these tariffs, six trading partners – Canada, China, the European Union, India, Mexico, and Turkey – responded with retaliatory tariffs on a range of US agricultural exports, including agricultural and food products. From 2018 to the end of 2019, US agricultural exports were reduced by over $27 bln because of these retaliatory tariffs, with the steepest reduction in exports to China. In fact, the majority of revenues raised by the 2018 Trump tariffs went to subsidize farmers for the loss of revenues from the retaliatory tariffs.

- Hence, the importance of analyzing retaliatory tariffs as part of any tariff program. Retaliatory tariffs can lead to significant economic disruptions, affecting GDP and employment.

- Retaliatory tariffs disrupt established trade relationships and supply chains. For example, China’s retaliatory tariffs on US goods, including agricultural products, have affected US exports and led to increased costs for US producers.

- Retaliatory tariffs often strain diplomatic relations between even friendly countries. The imposition of tariffs by the US on Canada, Mexico, and China has led to tensions, with these countries responding with their own counter-tariffs, even despite the existence of trade agreements that Trump negotiated.

- Retaliatory tariffs can significantly affect local economies, particularly in regions heavily reliant on industries targeted by such tariffs. For example, China’s retaliatory tariffs on US exports could impact thousands of jobs in regions like North Dakota, Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, Alabama, and West Virginia.

- In the US, retaliatory tariffs can lead to increased costs for consumers and businesses, such as on the steel and aluminum industries. These tariffs can lead to higher prices for goods and reduced competitiveness for US manufacturers along those supply chains, even though the impetus of placing steel and aluminum tariffs was the protection of jobs for aluminum and steel producers.

- Finally, reciprocal tariffs on the part of the US would essentially mean the US is now outsourcing tariff policies based on actions of other countries. It would require managing tariff rates across 200 countries and millions of individual products. Indiscriminate reciprocal tariffs can lead to applying tariffs to essential imports even if the US does not export similar goods. Any system of tariffs that does not account for the particulars of individual trade relationships will produce less than desirable outcomes.

In conclusion, retaliatory tariffs pose significant challenges and have far-reaching implications for international trade, economic stability, and political relations. To exacerbate this argument, for all his claims in the power of reciprocal tariffs, Trump does not appreciate (and even ignores) the value of free trade agreements that guarantee zero tariffs on both sides.

Globalization and the Decline of Manufacturing: A Misguided Pursuit of Protectionism

The decline of manufacturing in the US has been a central theme in political discussions, with efforts to revive the sector often framed as a pathway to economic renewal and revitalization. However, the steady erosion of manufacturing employment is not a unique phenomenon found only in the US – in fact, it is a trend observed across all developed economies. Even nations like Germany and Japan, which implemented policies aimed at preserving their manufacturing bases, have been unable to prevent this structural shift away from manufacturing and into services. These policies, similar to those advocated by Trump, have largely failed to shield domestic manufacturing industries from broader economic forces under the forces of globalization and comparative advantage.

One of the unintended consequences of aggressive manufacturing protectionism is that it insulates domestic firms from healthy global free market competition. Countries that have relied on tariffs and trade barriers to bolster their industrial sectors often miss out on technological revolutions because their companies are not forced to innovate in response to global market pressures. In contrast, the US, which remained more open to international trade and competition, has emerged as a leader in high-value, technology-driven industries. Attempts to regulate and shelter manufacturing with protective trade policies not only contradict basic economic principles but also risk undermining long-term innovation and prosperity.

Rather than focusing on reviving an outdated economic model, the US has excelled in developing high-value service sectors. The US runs a significant trade surplus in services, reflecting its strength in industries such as technology, finance, entertainment, and professional services. While concerns over national security and supply chain resilience are valid, the broader reality is that manufacturing, as a dominant driver of employment and economic growth, has become a relic of the past rather than a blueprint for the future. And concerns of national security can be alleviated using other means.

The theory of comparative advantage has played out as expected in the US economy. Over time, lower-value manufacturing jobs have shifted to countries with lower labor costs, such as China, while the US has specialized in knowledge-intensive sectors. In 1973, manufacturing accounted for over 25% of total US employment; by 2023, that figure had fallen to just 8%. This transition reflects a natural economic evolution rather than a failure of policy.

Empirical evidence demonstrates that companies do not innovate because of government incentives or tax breaks, but rather in response to competition. Over the past five decades, globalization has broadly benefited the US economy – providing consumers with lower-cost goods, fostering technological advancement, and creating high-value jobs. Protectionist policies threaten to upend this dynamic, redistributing benefits to a narrow set of industries, such as steel and aluminum, while imposing higher costs on consumers and businesses alike.

Rather than pursuing policies that seek to reverse globalization, the focus should be on ensuring that the US remains at the forefront of innovation. Protectionism may provide temporary relief to select industries, but it ultimately weakens the broader economy and its costs are broad-based. The US’ long-term prosperity will not come from clinging to the past, but from continuing to lead in the industries of the future.

An Expository Analysis of the Investment Management Implications of Trade Policy

In today’s rapidly evolving geopolitical landscape, tariffs have become more than just tools of trade policy – they are indicators of deeper structural conflicts in the global economy, particularly with China. At the heart of this confrontation lies China’s mercantilist economic growth model, which relies on state subsidies, currency manipulation, overproduction, and export-driven growth.

Since the rise of Xi Jinping, and in particular after 2016, China has focused on developing high-end manufacturing capabilities, such as electric vehicles (EVs), batteries, and solar technologies, without meaningfully rebalancing its economy toward domestic consumption. In just five years, China went from exporting hardly any vehicles to becoming the largest vehicle exporter in the world, with the capacity to build one-half of the new global vehicle demand each year. BYD sales of electric vehicles have completely eclipsed sales of Teslas. This imbalance has led to the flooding of global markets with Chinese goods, exacerbating trade tensions with countries like the US, EU, Japan, India, Brazil, and others who are even members of China’s Belt & Road Initiative.

To address this glut of production and limited domestic demand, China has expanded its global footprint through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative, often exporting its mercantilist practices to member countries. The response from the rest of the world has ranged from targeted tariffs to diplomatic pushback, with calls growing for a coordinated, multilateral strategy to pressure China into adjusting its economic model. Merely applying unilateral tariffs may yield short-term political wins but fail to achieve systemic change and long term benefits. Instead, this paper emphasizes strategic collaboration among trade allies, leveraging tariffs in a surgical and targeted way to force structural reforms in China’s economy.

While the focus on China remains central, broader geopolitical tremors are also reshaping global alliances—particularly between the US and Europe. President Trump’s hostile rhetoric and erratic policy stance toward Europe and NATO member countries have led to increasing skepticism among European allies regarding the reliability of American support – both economic and security. Consequently, major European powers – including Germany, France, and the UK – have begun rethinking their defense strategies. The move toward greater autonomy, including the potential formation of a European coalition to support Ukraine independently of the US, marks a fundamental realignment of transatlantic ties. Strategic discussions have even explored new forms of cooperation with China, a once-unthinkable proposition.